Cherry red and roughly the size of a small ocean liner, the Fury -- which I named "The Red Baron" -- was a one-way ticket to freedom. I could now go wherever I wanted, whenever I wanted. You know, as long as my mom was cool with it and it was before curfew.

I purchased the Fury on a Friday night in early July. If I recall correctly, it cost around $800, which seemed both like a small fortune and a ridiculously tiny price to pay for virtual independence. The bad news: I didn't have my license yet. I had actually failed my first driver's test a couple weeks prior.

This still pisses me off. I was kicking ass on the test and then, at the very end, right outside the DMV, the woman administering the test asked me to parallel park. I nailed that too, and I naturally assumed I'd passed with flying colors. However, she failed me. When I asked why, she said it was because, while turning left onto Markland Avenue -- one of the main streets in Kokomo -- my left tire had passed ever-so-slightly through the opposite lane and cut over the front edge of the yellow line separating the two sides of the street.

"If there had been a car there, you would have hit it," she said.

"But there wasn't a car there," I replied.

"True, but there could have been."

"But...but...people do that all the time," I said.

"Yes, but new drivers shouldn't," she answered. "I think having to retake the test will break you of that bad habit, don't you?"

Seriously, I could have choked a bitch.

The Tuesday after buying the Fury, I went in to retake my test. I got the same instructor, and yes, she remembered me. She literally had me drive a circle around the DMV and passed me.

"I trust you learned your lesson?" she said.

The only lesson my 16-year-old self learned was that people in a position of power can and probably will screw with you. But at least I was now a licensed driver.

Now, I had taken the test in my mom's car -- a 1987 Buick Somerset -- because it was much smaller than the Fury and therefore easier to drive under testing conditions (that is, if I needed to parallel park again). When I got home, the first thing I did was jump into the Fury. Jammed in the key. Turned the ignition.

Nothing but a dry cough-like sound.

See, on Friday night, shortly after getting my new car home, my buddy Greg had come over and -- since I couldn't actually drive us anywhere yet -- we had spent the night sitting in the car listening to the tape deck...which was wired directly to the battery. That meant the radio could be on and running even when the key wasn't in the ignition. Sure enough, I'd left it running and the battery was now deader than Shaq's bathroom scale. Dead and so old, in fact, that jumping it only blew a little rust off the connectors.

One battery replacement later, I was finally on the road.

But I wasn't taking too many joy rides. Not at first anyway. About the only places I drove to were my friends' houses -- it kind of rankled them at first that I wouldn't drive us to the mall or the local cruising strip -- and my "home court." This was a little basketball court behind Boulevard School, my old elementary school, which just so happened to be about two blocks away from my high school, Kokomo High School.

The Boulevard court had some definite downsides. The backboards were made of the creakiest wood imaginable, and the rims were composed of the clangiest iron in the known universe. The blacktop surface of the court was covered in dead spots and shallow, nearly imperceptible depressions that tended to collect water. Oh, and it was surrounded on three sides by nothing but corn fields. This meant that a) there was no protection from the burning summer sun (so I often had no choice but to shoot toward the sun from one angle or another) and b) there was no protection from the wind.

And, if you've ever played outdoors, you know the wind can be a real problem.

That said, the Boulevard court was also relatively private. Nobody liked to play there for the reasons outlined above and the fact that there was no three-point line. As a result, I could practice for hours upon end without being interrupted or even seen. And I was definitely in Learning the Game mode. And for that, I wanted privacy.

Since I didn't have any actual coaching, I decided to make Larry Bird my coach. I re-read Bird's autobiography, Drive. I re-watched Larry Bird: A Basketball Legend as well as every old Celtics game I had on tape. I went to Kokomo's only major bookstore -- Walden Books -- and found a copy of Bird's instructional manual Bird on Basketball: How-to Strategies From The Great Celtics Champion. (Still available used from Amazon.com!)

I read. I watched. I read and watched some more. I digested. And then I tried to incorporate Bird's concepts into my budding game.

Which brings us to...

The Pickup Rules

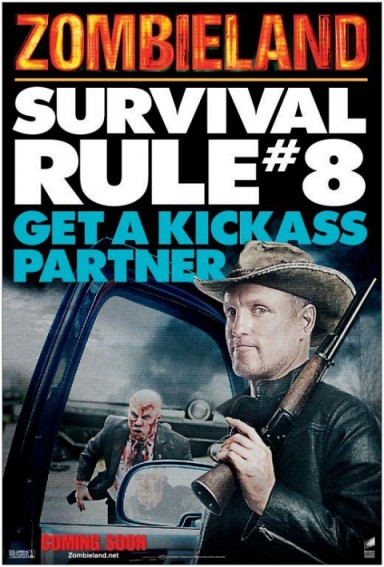

In case you haven't seen Zombieland yet -- and I highly encourage you to do so immediately if you haven't -- the main character, Columbus, is a painfully awkward nerd who managed to survive the zombie apocalypse by strictly adhering to a series of zombie-specific survival rules. For instance:

But long before Jesse Eisenberg was unintentionally (one assumes) fooling people into thinking he was Michael Cera -- they're entirely different people, I swear -- I was inventing the rules necessary for my survival in pickup basketball. I will be describing these rules throughout The Pickup Diaries.

Now...despite his reputation as a fearsome outside shooter, Bird's arsenal also included a wide variety of drives, dunks, layups, hooks and scoops. He also had some killer low post moves. That's why his career field goal percentage was just a shade under .500, and he probably would have finished above .500 if he hadn't limped through his final four seasons with bad back.

Just for kicks, here's Bird beating the Portland Trail Blazers left-handed. I'm not kidding. You might have heard or read about this one: Bird told teammates beforehand that being so great was boring him...and he he vowed to shoot left-handed all game. He didn't, but Bird still ending up scoring 22 of his 47 points using his left hand. I know. Awesome.

At any rate, Bird's shooting philosophy became the basis for my very first rule regarding pickup hoops:

Pickup Rule #1: Always take the highest percentage shot available.

Sounds obvious, right? So simple...but so very hard. I mean, you'd think everybody would do this. But take LeBron James and Kobe Bryant for example. They're probably the two best basketball players in the NBA, but they take an unbelievable number of crap shots. At times, it seems like they're stuck in permanent heat check mode. And they aren't alone. Lesser players do it (think Monta Ellis). Hell, even lousy players do it (for further reading, please refer to the collected works of Hughes, Larry).

Mind you, Bird wasn't without sin. He had the blood of a hundred bastard field goal attempts on his mangled hands. But in general, Bird tried to always get -- for himself or his teammates -- the highest percentage shot available. And for Larry Legend, that meant close to the hoop.

When Bird retired, he was perhaps the greatest three-point shooter in league history. Even today, he's considered the one of the all-time greats, in part due to his dramatic victories in the NBA's first three Long Distance Shootouts (1986, 1987 and 1988).

But in many ways, Larry hated the three and decried its use. This was because a) he felt it was a low percentage shot (which it is) and b) that if a team had a two-point lead at the end of the game, that team should never lose to a last-second shot. Which is kind of ironic, considering Bird won several games on last-second treys during his career.

However, despite this slight contradiction in philosophy and behavior, Bird's word was Basketball Law to me. For this reason, I never practiced threes. Never even attempted them while goofing around. To me, it was a waste of time that could be spent practicing shots I could actually use in a game. (For this same reason, I've never attempted a half court shot or developed any trick shots for HORSE, unless you consider a three-pointer from NBA range to be a trick shot.)

Therefore, all my shots were attempted from 15 feet and in. After all, I had almost grown to my full height of 6'3" -- I've often wondered whether I would have grown even taller had I not spent much of my childhood malnourished -- which made me a "big man" in pickup basketball terms. This meant that my game should be close to and going toward the basket.

I worked on every variety of layup I could think of. (Although it was quite a while before I realized the value of trying to develop my left hand...in fact, I'm still working on that.) I used my mental chalk to draw a 15-foot arc around the hoop and practiced shots from every angle. (However, due to dead spots and funky rims, I often avoided baseline shots, which would haunt me later.) And I worked on my inside moves.

Fortunately, I was a natural in the post due to decent footwork, a long wingspan (or, as my college roommate BadDave called them, my Gorilla Arms), and a soft touch. Plus, I had spent my formative years following the Bird-era Celtics. This meant hours upon hours of watch Kevin McHale put opponents into his torture chamber.

McHale -- yes, my last name is also McHale, no Kevin and I are not related -- had a seemingly endless array of low post moves. This wasn't exactly true. He had a set number of moves, but the moves had so many subtle variations that they seemed endless. These moves are actually described in stunning detail in The Book of Basketball by Bill Simmons, which makes the book a must-read for anybody who wants to became a killer post player in pickup ball.

And that was my life for the next two months. Endless, tireless practice. I practiced in the morning, the afternoon, and at night. I played in the sun, the wind, and in the rain. By the end of that period, I was knocking down a fairly high percentage of my shots, which made me feel pretty good about myself. After all, I had only just picked up the sport.

What I didn't (and couldn't) understand at the time was this: A large part of my early "success" was due to the fact that I had focused on a very specific and therefore very limited number of shots. Not to mention that every shot had been attempted against no defense. But these things don't matter when you don't know any better. I was confident. A little cocky even. And with the new school year fast approaching...

...it was time to take my game on the road.

No comments:

Post a Comment